“taking part in hobbies, learning a new language, knitting, puzzles and listening to music… will stimulate different areas of the brain and help with attention and concentration”.

But Alzheimer’s UK reports a mixed picture.

“Some studies have found that cognitive training can improve some aspects of memory and thinking, particularly for people who are middle-aged or older,” it notes. But “so far, no studies have shown that brain training prevents dementia”.

Indeed, it warns: “People should be cautious if they find commercial packages that claim they can prevent or delay cognitive decline as the evidence for this is currently lacking. Recently, one of the leading providers of commercial brain training games was fined for making false claims about the benefits of their product.”

That may be a reference to the US firm Lumosity, behind the computer “brain training” app Lumos Labs, which in 2016 paid a US$2 million (NZ$3.2m) fine levied by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) on the basis that it “deceived consumers with unfounded claims that Lumosity games can help users perform better at work and in school and reduce or delay cognitive impairment associated with age”.

Then the FTC’s director of consumer protection, Jessica Rich, went so far as to say that “Lumosity preyed on consumers’ fears about age-related cognitive decline, suggesting their games could stave off memory loss, dementia and even Alzheimer’s disease. But Lumosity simply did not have the science to back up its ads.”

But that doesn’t necessarily mean that we should all throw away our crosswords and sudokus, or delete our brain-training apps and programmes.

There is NO known pathway, as yet, to preventing dementia.

A recent analysis of 215 clinical trials supported by America’s National Institute on Ageing (NIA) showed that the “various cognitive training tools… can help older adults who are healthy or have mild cognitive impairment to improve cognitive health and perhaps their everyday functioning”.

Critically, it found that while the benefits were “modest in size”, they affected both the healthy “and those with mild cognitive impairment. This may mean that some forms of cognitive training can help reduce or delay the development of cognitive impairment and dementia”.

In Britain, a huge study called Protect, run in partnership with the NHS, is following thousands of people to find out, as lead researcher Professor Clive Ballard puts it: “which combination of [lifestyle] factors really work” in preventing or delaying dementia.

So, is Wordle a form of brain training?

And the answer’s no, not really.

Because players just get better at Wordle. Just as is with crosswords and Sudoku. But these activities DO exercise brain connections while you are doing them.

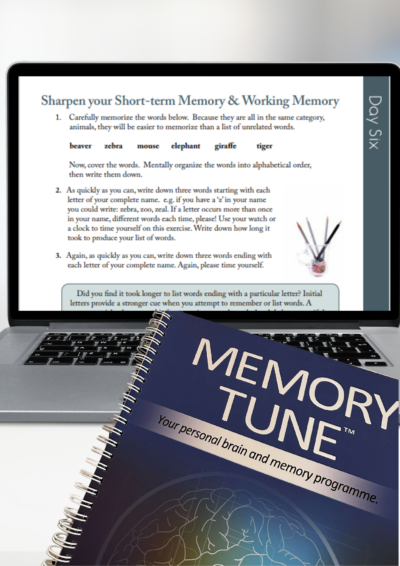

Brain training involves challenging all of the memory skills along with cognition, transference of skills and building cognitive reserve.

Brains were once thought to be immutable and unchangeable. But they’re just not.

Brain training can bring about measurable results:

‘A gain of ten years of function, so people in their 70s were performing more like their 60s, while people in their 60s were performing like people in their 50s.” Dr Henry Mahncke

There is no surefire way to prevent dementia, whether it is caused by lack of blood flow to the brain (vascular dementia), genes (Huntington’s disease) or, as in two thirds of cases, Alzheimer’s. But the research says that keeping physically and mentally fit might help delay the symptoms of dementia or improve symptoms when they occur.

So keep up with the puzzles, Wordle, Sudokus and especially, brain training.

Brain health is a lifetime health issue.

Do you play Wordle? What are your favourite ways to challenge your brain?

I find it difficult to retrieve thoughts and words but I do try Wordle . I do enjoy Wordfit and hopefully that helps my brain!

Anything that challenges you to move beyond everyday, routine activities is helping your brain. Well done!

I am taking medication – I am sure that it is causing me to lose words and I have to check my spelling more often. spelling, reading and talking have always been easy and a source of pride. Reading is fine but I feel there is deterioration in the speed of remembering words and I am less confident that my spelling is correct.

I am taking medication after a recent heart attack. I am sure the meds are causing me to lose words and I am checking my spelling much more often than I used to. My short term memory seems affected too.

Reading is fine, conversation and spelling are where I notice the changes most. I have always been a good speller (the spelling police type!!!). Names, and remembering where I have met someone, sometimes involves searching my memory – I remember visually – to link the face with the place. I am 74.